|

1/28/2020 0 Comments 14th century Hourglass gauntletIntroduction

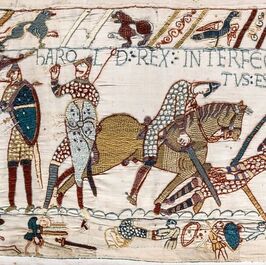

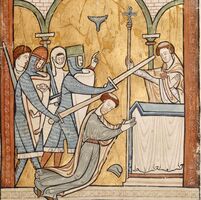

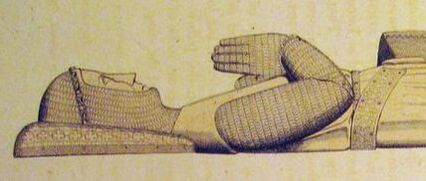

Early Form of hand protection: MailIn the 11th century, knight wore a hauberk (knee-length mail shirt) and a gambeson (aketon, doublet) underneath to protect his arm up to the fore arms, according to the Bayeux Tapestry. The protection to the hand, which was not mentioned in any literature in this period, was exceptionally rare. A knights had to relied mainly on shield and weapon's guard to protect his hands. Some observations suggest he might wore leather or padded cloth gloves for defense as these had existed few centuries in Europe. In the late 12th century, mail mittens rose to popularity as the sleeves of the hauberk extended from the elbow until it protect the entire hands. All of the fingers are in a single pouch with a separate compartment for the thumb. The padded cloth or leather palm was slitted, allowing the wearer to removed the mitten without removing the hauberk. Mail offered excellent protection against stab and slash weapon. And because of its flexibility, mail mitten did not hinder fighting capability much. In late 13th century, mail mittens became an independent piece of armor called mail gauntlets. In the Effigy of William de Valance, mail gauntlets separated from the hauberk. They protected individual finger; and by giving the wearers the full movement of the wrist, they increased precision and control of weapon. The sketch of the 14th century mail mitten in an effigy in Church of Schutz show the similarity of the mail mitten to our modern glove. It also suggests that knight wore a pair of leather gloves underneath or sometime above mail gauntlets. Hour-Glass Gauntlets

0 Comments

1/18/2020 1 Comment The Bascinet in the 14th centuryIntroduction: the bascinet

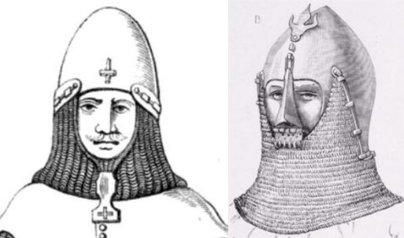

Bascinet Origin: The CervelliereThe origin of the bascinet is the hemispherical steel cap called Cervelliere. It was introduced in the late 12th century to provide protection from the tophead to the forehead of the European soldiers. Soldiers either wore it alone or under or over a mail coif. In the 13th century, it became a common practice for knight to wear a Cervelliere under a great helm. Overtime, the Cervelliere extended to the neck of the wearer, becoming the first bascinet. 1st Development: the Extension to the neckWhen the Cervelliere began to extend downward to the neck of the wearer, it became known as the bascinet. The earliest surviving bascinet is currently located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (the MET). It was created around the first quarter of the 14th century. Knight stopped wearing this helmet underneath the mail coif. Instead, he wore it over the mail coif as demonstrated in the effigy of Sir Robert du Bois. The early bascinet did not have an aventail attached or a visor to protect the wearer's face in comparison to later bascinets. It is interesting to note that a series of small holes in the lower part of the 1325 bascinet were not meant to be attached with an aventail (Camail). They are places where the bascinet and the padded lining joint together by sewing.

2nd development: Aventails

3rd Development: Face protection

1. The Bretache Bascinet: The bretache is a nasal guard that attaches to the bascinet. Early bretache was made from riveted mail that connects to a aventail. It evolved to a piece of plate armor as in the illustration of from the monument of Ulrich Land Schaden. Some European knights wore a greathelm over this type of bascinet. 2. Visored Bascinet: The most advanced bascinet type in 14th century was the hounskull (pig-faced) bascinet. Many historical bascinets of this type were well preserved. There were two types of visored bascinet depending on how the visor attaches to the helmet. In the Klappvisor, visor was hinged at a single pivot in the center of the brow of the helmet skull. The double-pivot type the visor was attached to two pivots – one on each side of the helmet. Other than that, there were no significant differences between them. The visor was pointy in the nose area, so it could deflect incoming projectiles and weapon blows to the wearer's face. When in hand-to-hand combat, the visor could be lifted or even detached to provide the knight extra needed vision. It was because of the introduction of the visor, the practice of wearing a great helm over the bascinet was ceased to exist. Knights favored the light-weighted hounskull bascinet in battle while the great helm and its successors stayed in jousting tournaments. Successors of the BascinetThe bascinet continued its development in the next centuries into the great bascinet and eventually be replaced by the more advanced armets. The discussion about the great bascinet and armet will be discussed in future posts.

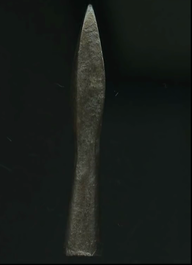

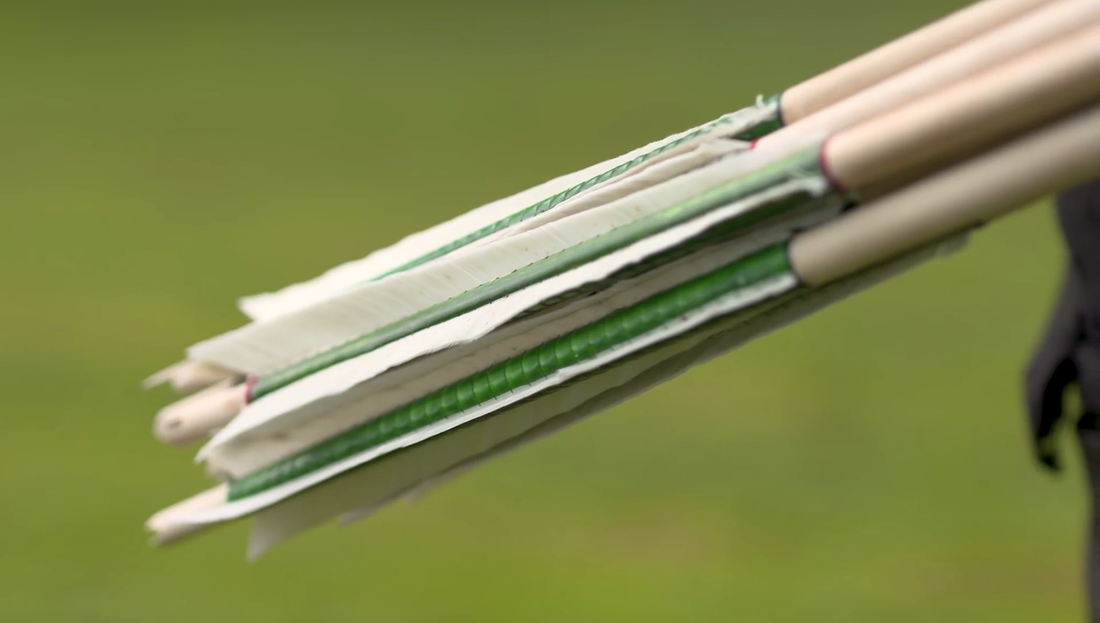

IntroductionThe battle of Agincourt 1415 implanted the idea that it were the skillful English longbowmen that defeated the numerous well-armed French knights. We are led to believe that the longbow was a marvelous technological advance of this period that they could shoot powerful arrows that pierce through plate armor. Sometimes history is not what it really is, but what we want it to be. We understand past events in accordance to what we wish to be. We d over-zealously defend aspects that fit our beliefs and downplay other important aspects. While the longbow was the subject of popular myths and legends, the importance of the newly addition of plate armors was largely underappreciated. A few decades before the battle, the first plate armors were created to strengthen vulnerable body areas that were already protected by mail (chainmail, maille). Afterwards, it became very popular among European Knights due to its effectiveness even though this significant event was largely ignored by history enthusiasts. In 2019, Tod Todeschini gathered a group of world class in their fields of expertise, armour, arrows, shooting and historical context to debunk the myth of the longbows. It is proven that plate armor was very capable of protecting the wearer against the powerful longbow. The original video can be find here Set up the experiment

Observations and resultsExperiment 1: Wrought arrow, not hardened, 25 m Observation: with the exception of the first arrow, none of the arrows ran through the armor. - The first arrow hit the low edge of the breastplate then skated to the mail area that was not protected by the plate. The first arrow pieced through the maille and the gamberson underneath. - The second and third arrow hit the plate hard, then were defected out the the breast plate Experiment 2: Wrought iron arrow, case-hardened 25m Observation: None of the wrought iron case-hardened arrow penetrated the breastplate. - The first arrow hit the breastplate hard to the point that the arrowhead was broken. - The second arrow was deflected by the breastplate - The final arrow hit the breastplate the hardest and was knocked back. There was a clear visible big dent on the plate. Experiment 3: Arrow to the Jupon over the breastplate French Knight in the period often wear a piece of fabric over the breastplate, called jupon. The jupon significantly altered the projectile of the arrow Observation: No arrow pierced through the breastplate. The jupon captured all the arrowheads - The first arrow hit the center of the breastplate, but did not go through the plate. The arrow was held in place by the jupon - The second and third hit the center hard enough to break the arrowheads. In both case, both the arrow shafts were knocked back, leaving the arrowhead in the jupon. Experiment 4: Modern Steel case-hardened Arrow head, Distance 10 m (best chance for penetrating breast plate) Observation: Not even the modern steel case-hardened arrow could punch through the armor. But it did leave the biggest dent on the breastplate. Conclusion:

Credits:

Dr Tobias Capwell - Arms and Armour Curator, The Wallace Collection Joe Gibbs - Archer and bowyer https://www.facebook.com/Hillbillybows/ Will Sherman - Fletcher – http://www.medievalarrows.co.uk Kevin Legg - Armourer - http://www.plessisarmouries.co.uk Chrissi Carnie - Fabric armour – http://www.thesempster.co.uk Tod Todeschini - Host - http://www.todsworkshop.com http://www.todcutler.com 12/17/2019 1 Comment Churburg-Style Armor (14th Century)In the 11th to 13th century, mail (maille or chainmail) armors were the dominant armors in Western Europe. Knights, Nobles and even kings wore mail in battles as mail armors were very effective against sharp weapons. New developments in the 14th century ends the popularity of mail. Mail no longer provided sufficient protection for the wearer. Thus armorers of this period began the transition to plate armor as pieces of plate were used to reinforce in the most vulnerable area of mail armor. Compared to mail, these reinforced plates provided much needed protection against all type of weapons, including blunt weapons. Still, plates did not cover the entire body of the wearer yet, so mail was used to cover these areas. Armorers in Northern Italy were in the lead as they produced the most quality plate armors. These armors were so popular that many knights from England, France, Germany and Spain purchased them. The armory of Churburg Castle still preserves a large number of armor pieces in this period. Thus historians often use the term Churburg-Style armor (Churburg Armor for short) for Italian armors made in this period Armor of Ulrich IV von Matsch. Castle Churburg Armory. The visored bascinet helmet (bascinet for short) was the helmet of choice in the Churburg armor and it remained a solid choice for knights over the next 150 years. Its design helped deflect weapons and projectile attack to the wearer's face and neck. (Click here to know more about the bascinet) The "houndskull" visor protected the knight's face by deflecting unexpected and fast moving projectiles like arrows and lances. When fighting in close combat, it was more advantageous for the knight lifted the visor to see things better. Riveted aventail which attached to the bascinet to provide the protection to the neck and shoulder of the knight. In later period, the aventails was also replaced by plate gorgets. Around 1350s, breastplate was introduced to strengthen the torso area. Compared to later centuries, breastplates in this period did not covered the entire torso. The breastplate had a large central plate riveted together with some small plates warping around the side to the back of the wearer. Leather straps were used to to keep the breastplate in place. Sometimes, a V-shaped metal piece was riveted to the central plate to stop thrusting weapon sliding to the wearer neck. As time passed, plates armor eventually cover the other part of the body, such as arms, hands, and legs. This armor below was restored in 1920 which individual elements (dated in the early 15th century) discovered in the ruins of Venetian fortress on the island of Eubora. The armor is kept in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

|

Viet LeThis section is dedicate to the understanding of armor. |

Proudly powered by Weebly